The Good Men Aren’t Gone, They’re Delayed

And that means women can't afford to wait in the marriage market.

Everyone is asking: where have all the good, marriageable men gone? Or, more accurately: no one is asking, since everyone has their answer on who’s to blame for this.

Antifeminists say: the men are just as good, but women’s standards are unrealistic. They took all the college spots and high-paying jobs, but still demand a husband who is richer and more accomplished to impress their friends. And blame hookup culture too: girls hook up with Chad once and expect a ring from a guy who looks like that.

Feminists say: the standards haven’t changed, men just aren’t stepping up. Women just want an emotionally literate provider, and everywhere they see man-children. Instead of competing in the modern marketplace with educated women, men retreat to insular status games like video games or crypto schemes. And blame hookup culture too: since casual sex is so easily available (if not to engage in then at least to fantasize about) that they feel no pressure to become worthy husbands.

Both are right in some ways. People have extremely high expectations of marriage — especially women. Yet simultaneously fewer people seem interested in marriage — especially men. A woman looks at her peers and notices more women who are ready to be wives than men ready to be husbands, in both ability and desire.

But both the “women should lower their standards” and “men should step up” camps are making the same mistake: treating the dating pool as fixed. People’s marriageability and their standards for a partner change a lot with time. Few 18-year-olds know what they’re looking for in a spouse, even fewer have the proven traits a good spouse wants.

If we add time as a variable, we can explain much of the mystery:

Where the good men are.

Why it’s straight women who complain about the difficulty of finding a marriage even though — since every straight marriage involves one of each — it must be equally difficult for both sexes.

Incels.

Age-gap relationships.

Why women feel that dating suddenly becomes impossible at 35, even though they are as attractive as ever, skilled and confident, and have (with some technological assistance) many years of fertility left.

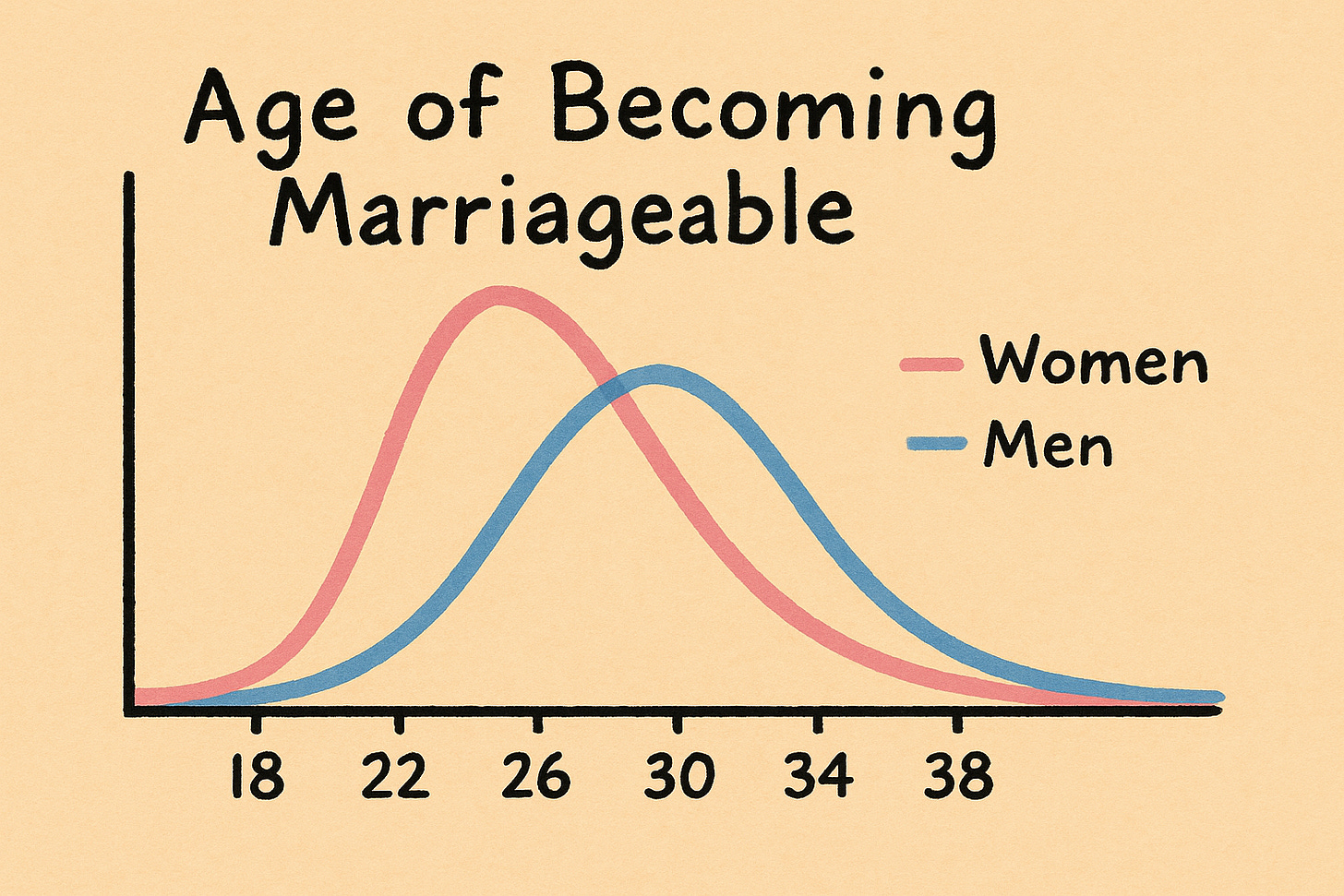

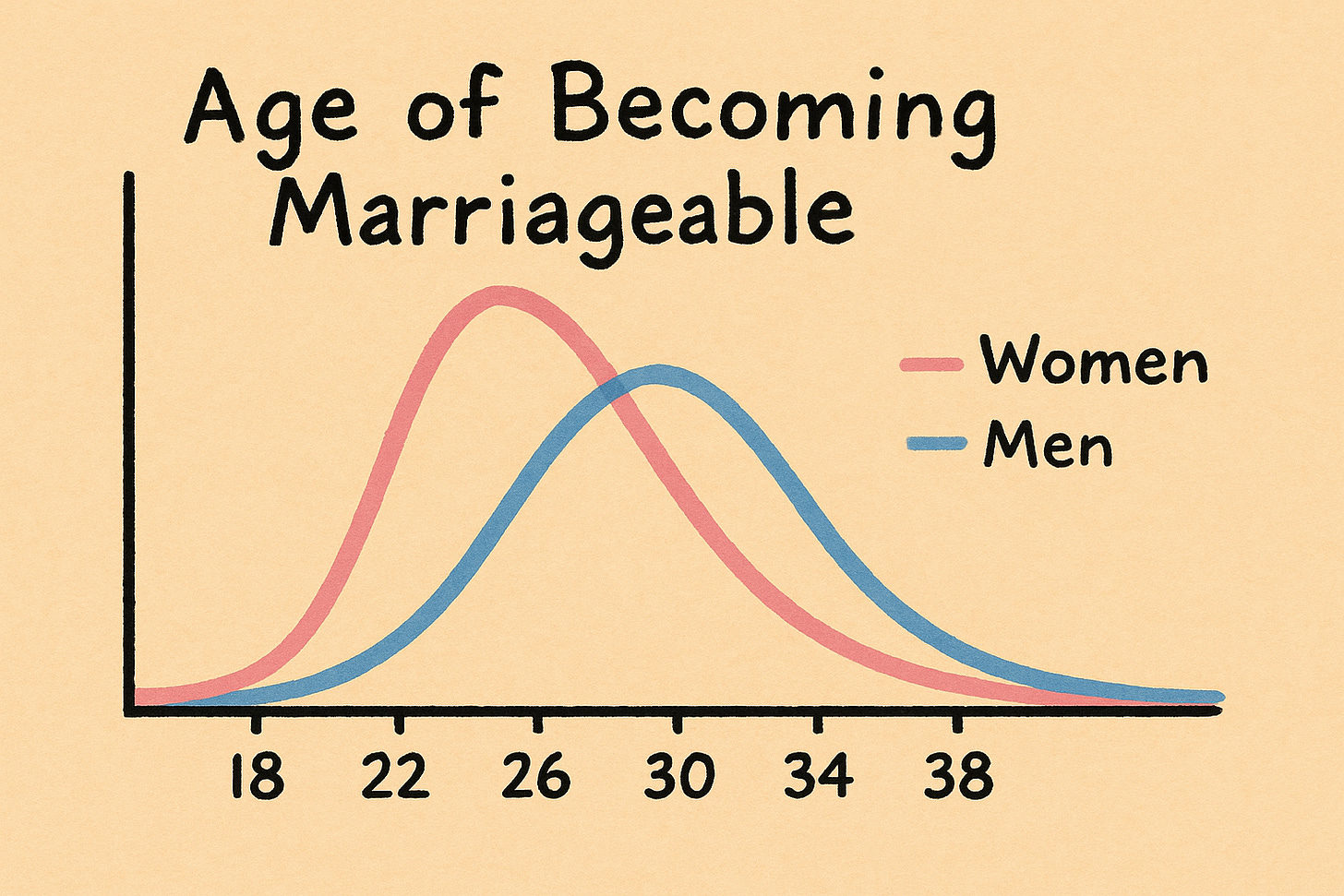

People become “marriageable” — fulfill the list of criteria the opposite sex expects in a spouse — at different ages. The questions above are answered with a single observation: men become marriageable at a later age, on average, than women.

Man Lag

What makes a man “marriageable”? Depends who you ask. For the Hamar of Southern Ethiopia, it’s being able to run across the backs of several bulls tied together four times. This requires considerable physical prowess, but it can be accomplished by guys as young as 15 or 16. Once he has “jumped the bulls”, the boy becomes “maza” and is eligible to take the first of several wives.

What if you ask educated Western women? Aside from fixed physical traits like height or length, the first three things they’d list would be:

Emotional intelligence and communication skills

Financial stability and a clear career trajectory

Willingness to commit

There are approximately zero 16-year-old men in the West who satisfy these basic requirements. All of these contribute in various ways to the divergence of marriageability clocks between women and men.

Women develop the soft skills that are relevant to marriage much earlier than men because the same skills — empathy, supportiveness, communication, awareness— serve a girl in a female peer group. In contrast, boys’ hierarchies reward boldness, gregariousness, humor, and physical prowess — valuable traits, but not ones that demand much emotional intelligence. A man needs to learn the latter over time, often from frustrated girlfriends who leave him slightly improved for the next one.

Financial stability often means a white-collar career; these require a lot more years in education, more years to get established, and more years to pay off the debt. It also takes longer to prove that you’re on a stable career, with Americans staying less than 4 years on average at a job. Even if a guy has all the traits it takes to make a good living, the inherent uncertainty of the modern economy means women will wait longer until they’re sure.

What of a young man in possession of a good fortune, must he be in want of a wife? Not necessarily.

Women generally select for short-term partners on the basis of the same traits they look for in husbands. Young depressed guys with no male friends are unmarriageable and, as a consequence, unfuckable. But a socially fluent guy in his twenties with a job and a bit of courage can find relationships of any length he desires. Outside of conservative communities like Mormons, he faces little pressure to settle down. His male friends, especially the ones who aren’t marriage-ready themselves, will nudge him to preserve his freedom to party, travel, and hang out.

Longer education, extended adolescence, and the prevalence of premarital sex delay women’s marriageability too. But women develop emotional skills earlier, don’t have to prove their breadwinning, and they feel the pressure of the biological clock. All the modern trends that push maturation to later ages push guys further back than women.

Let us summon the old spirit and put a number on it. Extrapolating from average age at marriage and other trends, I estimate that the median woman becomes wifeable at 26, while her future median husband only comes online at 30. Four years is a conservative estimate of the husbandability delay, especially if you ask single 30-year-old women. As we shall see, even a modest gap like this will have profound effects on the dating landscape.

Mind the Gap

There’s an equal number of men and women in the population, and an equal number within each marriage — one of each. So how come it’s women who predominantly complain about the difficulty of finding a husband?

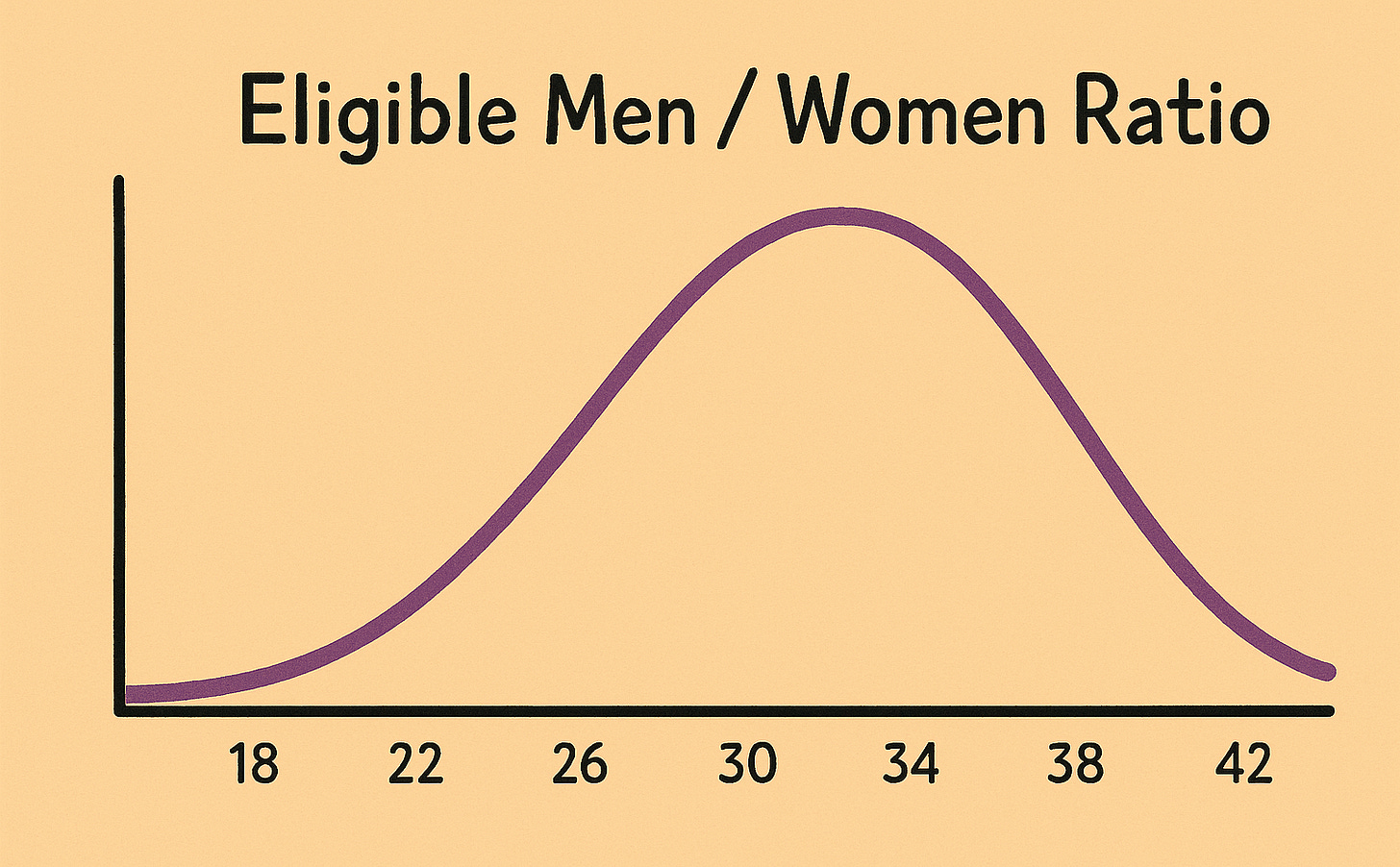

It’s all about the delay. Women enter the marriage market earlier than men, but leave at the exact same rate of one per wedding. For any given age, eligible wives outnumber eligible husbands. This makes each woman feel that the odds are stacked against her.

Overall, this handicap is offset by the fact that women spend longer on the marriage market, not only playing the numbers game but also learning with practice to recognize and seduce the right men. But this also means they have a longer experience of frustration with the undersupply of husbands. Given the favorable ratio, men who graduate into husbandability get hitched before they have time to complain. When a guy says there are no good wives out there, we assume he’s not much of a catch himself.

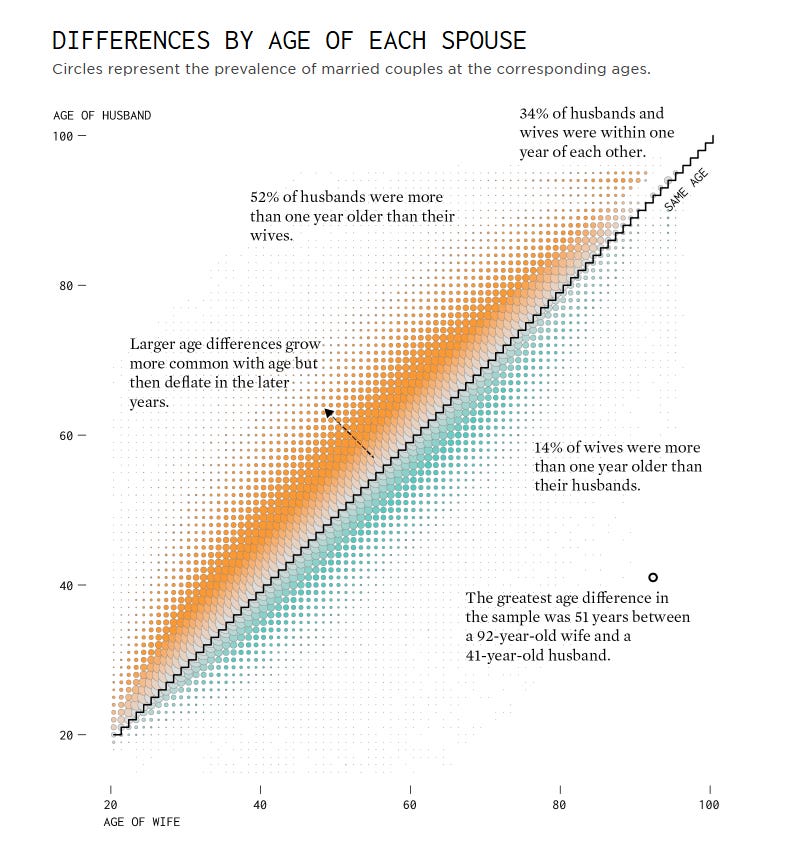

The chart also explains the observed age-gap pattern in marriages, without having to resort to reddit words like “nubile” or “breeding potential”. That pattern is that men tend to be older than their wives on average and that the gap grows with husband’s age.

“Age gap discourse” brings to mind guys in their 30s picking up college girls, but these relationships are exceedingly rare. The average 31-year-old husband marries a 28-year-old wife (and still has to deal with age gap discourse). We see the widest distribution of husband ages for wives at 40, right at the tail end of biological fertility. A lot of these women end up marrying men who are 50 or older.

If a guy enters the market in his late 40s (or re-enters it after a divorce), he will still find a favorable ratio and a pool of younger women because other men are becoming marriageable even later, if at all. He can afford to be selective on women’s relative youth.

Not a Wall, but a Cliff

In the original chart, I assumed a Poisson distribution for becoming marriageable with age, one with relatively narrow tails. Under this assumption, after age 28 more men than women are added to the pool of eligible singles and the ratio for women slowly improves.

This, however, is not the actual experience reported by women. The Atlantic ran the famous All the Single Ladies cover story by Kate Bolick 14 years ago. The experience of looking for husbands in one’s 30s has not improved since then:

We took for granted that we’d spend our 20s finding ourselves, whatever that meant, and save marriage for after we’d finished graduate school and launched our careers, which of course would happen at the magical age of 30.

That we would marry, and that there would always be men we wanted to marry, we took on faith. How could we not? One of the many ways in which our lives differed from our mothers’ was in the variety of our interactions with the opposite sex. […]

But what transpired next lay well beyond the powers of everybody’s imagination: as women have climbed ever higher, men have been falling behind. We’ve arrived at the top of the staircase, finally ready to start our lives, only to discover a cavernous room at the tail end of a party, most of the men gone already, some having never shown up—and those who remain are leering by the cheese table, or are, you know, the ones you don’t want to go out with.

The article echoes second wave feminists who argued that marriage is a bad deal for women, subordinating them as housemaids to ungrateful men. These arguments don’t seem to have chased many women out of the marriage market, otherwise the remainder would have an easier time. They seem mostly to help women come to terms with an increasingly hopeless dating market in their 30s. A market in which “most of the men have gone already” and, more importantly, some “have never shown up”.

Here’s how that market looks like for a woman:

For this chart, I ran a simulation with a couple of additional provisos:

Half the eligible men get into a marriage-bound relationship each year, taking themselves (and their wives) off the market.

10% of men don’t become marriageable at all, at least not in the time window that’s relevant for women who want to raise children.

If we remove just 10% of men from the under-40 marriage market, the dynamic in women’s 30s changes drastically. Instead of the singles ratio slowly edging towards parity, it drops off a cliff in their mid-30s.

Like Ms. Bolick, many young women don’t feel a rush to get married in their 20s because the ratio keeps improving in their favor: more men become marriageable each year than are taken off the market. But this flips past 30: most of the men who were gonna become husbands have already met their wives, and the shrinking pool of singles turns the ratio sharply against women.

The just-world fallacy creates a lot of psychological resistance to accepting the simple logic of supply and demand. People feel that on some level, everyone must get what they deserve and deserve what they get. If you can’t afford the house you want then either the system has judged you to be morally deficient as an earner and house-buyer, or else the system is morally corrupt for depriving you. People don’t want to accept that house prices are driven by impersonal forces that pass no judgment on anyone’s character.

This moralizing frame is even more tempting when it comes to dating. Either the single women are bad — entitled, ungrateful, and unattractive — or else the system is bad for inflicting broke, unmarriageable men on virtuous women.

This frame is both false and useless. You won’t shame an unpleasant loser into suddenly transforming into an attractive partner. And you certainly won’t shame women into manifesting husbands out of thin air. Women in their mid-30s are very marriageable — smart, caring, all looking young for their age — they’re just late.

I get why this is enraging for women, especially since the very men who refuse to demonstrate any husbandly qualities are the ones telling women they’re simply no longer hot enough to marry after 30. Being hot has little to do with marriage, and can even be a detriment. And insofar as it matters, a guy who’s actually thinking about spending the rest of your lives together and not just trying to neg down women’s mate value cares how good you look for your age. He’s not out there proposing to 18-year-olds as if they’re gonna look 18 forever.

It does feel unfair that the delay in men’s marriageability puts extra pressure on women to look for husbands early instead of enjoying their twenties carefree. But life is no picnic either for the man who fails to become husband-material, whose unattached lifestyle becomes just a little sadder and lonelier with each passing year.

The diverging timelines harm both the retarded man and the woman who’s waiting for him in vain. I want to help both.

I’ve written a lot for the former. I’ve tried to help guys get rid of the bad narratives that stand in the way of truly engaging with women and give some general guidance on practicing that engagement. I’ll have a lot more to say about what makes a man husband-worthy, though ultimately every man creates and discovers his own attractiveness through his own agency.

Here I have some market-based advice for women facing the husband cliff, offered at a fair market price.